Explanation of Auroral Sounds

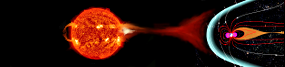

It is very likely that the sounds sometimes heard during auroral displays are produced in a similar way to the rare examples of instantaneous sounds from very large meteor fireballs, which were a mystery for more than two centuries. Very briefly, the turbulent plasma wake of the fireball excites electromagnetic waves in the Earth-Ionosphere cavity. The allowed modes lie in the kilohertz region of the spectrum. In the case of a fireball as bright or brighter than the Moon, megawatts of electromagnetic energy are produced and the electric vector is strong enough to excite acoustic vibrations in suitable objects, such as loose hair or frozen pine needles. The resulting sounds are heard as hissing, swishing or crackling by anyone in close proximity.

This explanation was developed by me to explain the widely perceived sounds from the huge New South Wales fireball in 1978. It was published in 1980 in the SCIENCE journal (Volume 210, pages 11-15). I was quickly able to prove in laboratory tests that rapidly varying electric fields could be heard provided there was something near the observer to act as a transducer. Even wearing a pair of glasses could raise a subject's threshold by 3 or 4 decibels. Later tests with mundane materials in an anechoic chamber verified that all sorts of objects could respond to rapidly fluctuating electric fields and produce faint sounds.

Detection of the ELF/VLF electromagnetic radiation from a meteor fireball was a much harder problem because such events are very rare. The Japanese succeeded, publishing proof of the existence of such radiation in 1988. This difficult feat has since been repeated by a team of Canadian astronomers using a video recorder. These have finally laid to rest the fallacious conventional wisdom that instantaneous fireball sounds are psychological in origin.

The same is probably true for auroral sounds. They only occur during extremely intense auroral displays, when, according to Olsen (Pure & Applied Geophysics vol 84, 1971) abnormally high electric fields have been measured. Very rapid fluctuations in such fields excite the audible sounds if suitable transducer materials are present. I am sure that attempts to record auroral sounds on a tape recorder, with a microphone lying on the snow, failed because there was nothing nearby to act as a transducer. If the microphone had been placed under a pine tree, instead of out in the open, the result may have been very different.

A similar process explains the occasional report of a person hearing a "vit" or "click" at the instant of a lightning strike before the crash of thunder. Also explained are the rare reports of earthquake sounds just before the seismic shock and, I suspect, the alarm of animals at such times.

Two Chinese astronomers have found old official records reporting that the Comet de Cheseaux, in 1743, produced audible sounds. This was one of closest cometary approaches on record. If the comet's charged particles or magnetic field interacted with the magnetosphere, VLF waves may have been generated to produce electrophonic sounds at ground level.

These findings open up a whole new field of scientific inquiry which I call geophysical electrophonics. There are no commercial applications in sight yet, but the scope for interesting research is immense.

This page was kindly produced by Colin Keay from the University of Newcastle in response to the page Have You Heard an Aurora?